Opals

I used to think opals were boring, whitish/pinkish things you got when you were twelve. Then I went to Australia...

WOW! Opals, it turns out, are rarely sickly white. They are among the most fascinating and beautiful stones in the world. Like snowflakes, no two opals are identical. Every real opal you buy is a one-of-a-kind piece. Beautiful opal comes from all over the world - and each place produces a different kind of opal. Selecting just one stone can make your head spin!

Opals for jewelry come in four basic forms.

SOLID OPAL: Sometimes an opal layer is thick enough to be cut out of the host rock and cut, shaped and polished separately. Even truly excellent white opal is expensive as a solid piece. Solid Lightning Ridge black opals (from one tiny region in Australia) can be many hundreds of thousands of dollars.

DOUBLETS: A doublet is a slice of opal on a backer. Usually the backer is made of ironstone, the normal host rock in Australia. Sometimes backers are made of onyx or other material. The opal layer is thick enough to give you the depth and play-of-color for which opals are noted. It is also thick enough to chip or crack if mishandled - just as solid opals do.

TRIPLETS: A triplet is essentially an "opal sandwich". It is a slice of opal between a backer layer and a clear upper layer, often made of quartz. A triplet is fully protected from chips, flakes and cracks by being entirely encased in harder materials. Triplet opals may have the play-of-color that is desired, but they look "glassy". It is also very easy to piece opals together in the midst of that sandwich.

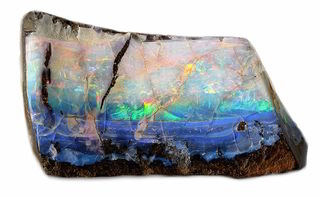

IN MATRIX: Most of the world's opals form in thin crevasses between layers of rock. They are not necessarily thick enough to be removed from the host rock nor are they necessarily in continuous "veins". Opals-in-matrix are called various things based on where they come from. In Australia, for example, they're called Yoweh Nuts (roundish) or boulder opal. People love to imagine pictures in the opal against the matrix.

Opals are as much as 15% water. They're are soft stones, so you need to take special care when using them. Whenever possible, surround them with "bumpers" so the edges don't chip. NEVER put them in an ultrasonic cleaner. Wipe them carefully with dish soap and warm water. Use a soft toothbrush on the setting. Wrap your opal jewelry before putting it away rather than simply dropping pieces in your jewelry-box. You'll be able to enjoy your opals for many, many years.

Picture credit:

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Opal_nz_hg.jpg

Source=own work |Date=2008-01-18 |Author=Hannes Grobe

Wrapped Faceted Stones

Transparent and translucent gemstones usually have facets that let light into the stone. The number and angles of the facets control how light bounces around or sparkles in the stone.

A "round brilliant" cut diamond, the kind you usually see in engagement rings, has 58 facets. Always. How well they're done (angled and polished) is one of the "4Cs" of diamond-buying - the "cut".

A "round brilliant" cut diamond, the kind you usually see in engagement rings, has 58 facets. Always. How well they're done (angled and polished) is one of the "4Cs" of diamond-buying - the "cut".

Then comes a problem. You have to put the stone in a setting so you can wear it. Settings generally close off sources of light to the stone. This is why most gemstone setting are open in the back behind the stone. Better settings often have filagree work and an openwork undergallery to let still more light reach the stone from a different direction.

A second common way of getting more light into gemstones is to set the stone "high". You are probably familiar with at least one kind of "high" setting. The quite-common Tiffany-style setting lifts the stone using four or six thin prongs. Most engagement rings are done in this style.

At Simple Elegance, we've gone Tiffany-style one better. We've removed the fixed setting entirely. We're specialists in wrapping larger faceted gemstones. Wrapping with thin silver or gold wire leaves almost the entire stone open to light coming from all directions. This gives the stone the opportunity to show itself off, giving our wrapped, faceted gemstones unique "pop" and special sparkle.

At Simple Elegance, we've gone Tiffany-style one better. We've removed the fixed setting entirely. We're specialists in wrapping larger faceted gemstones. Wrapping with thin silver or gold wire leaves almost the entire stone open to light coming from all directions. This gives the stone the opportunity to show itself off, giving our wrapped, faceted gemstones unique "pop" and special sparkle.

Check 'em out. You'll see what we mean.

Agates And Jaspers

These two kinds of stone are linked by far more than their beauty and variety. Essentially they are slightly different forms of quartzes.

These two kinds of stone are linked by far more than their beauty and variety. Essentially they are slightly different forms of quartzes.

When we think of quartz at all, we usually think about the neat crystals that are sometimes found in the earth or inside geodes or other rocks. These are the six-sided crystals that form many of the semi-precious stones that we facet and use in jewelry. (Check out our section on "Faceted Stones".)

Agates and Jaspers are from the other branch of the quartz family, microcrystalline or cryptocrystalline quartz. Their branches of the family tree has tiny crystals, 'way too small to be seen by the unaided eye. Because quartzes are so common, different kinds of agates and jaspers are found in many locations. Many are named for their patterns, for where they form within the Earth's crust or for where they have been found by people. As is true of other gemstones, the different colors are created by the trace minerals included in the basic stone.

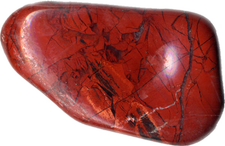

Agates and jaspers have unique patterns and colors that depend on how and where they were created and what trace elements happened to be in the water that seeped into the host rock. Many types have their own names - even though they are both types of chalcedony. Blue Lace Agate comes in stripes of different shades of light blue, for example. Crazy Lace Agate looks something like a Jackson Pollock painting done in browns, rusts and related colors. Poppy Jasper is an intense red with bits and veins of clear and very dark stone throughout.

Thinking about a geode is the easiest way to think about how agates and jaspers form. Gas bubbles in the original molten lava leave cavities in the rock as the rock cools. Nice round bubbles eventually became geodes or "thunder eggs". Spaces between rocks became pockets or veins of other material. Over years and years, water seeps into the cavities, bringing with it dissolved minerals. Alkaline elements in the water eat away at the original rock while the silicates and trace elements remain inside, forming layers of different-textured and different-colored stone.

Agates are usually at least partly translucent. Jaspers are generally opaque. In addition, while agates are rather orderly, jaspers are subject to repeated upheavals. This results in inclusion upon inclusion or heating and reheating. In either stone, the multicolors and the surprise upon seeing the particular stone gives them their value. People love to interpret the "pictures" they see in these stones.

Picture credit: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Agatebots.jpg#globalusage

Jaspers +

These types of stones are forms of quartz. But while we know quartzes mainly as crystals — amethysts and citrines and the like — or from their "stuff-in-quartz" inclusions, agates and jaspers have crystals so tiny that they can't be seen as crystals. "Cryptocrystalline" quartz is the proper term. Agates and jaspers are part of the chalcedony group, and it's often difficult to tell them apart.

These types of stones are forms of quartz. But while we know quartzes mainly as crystals — amethysts and citrines and the like — or from their "stuff-in-quartz" inclusions, agates and jaspers have crystals so tiny that they can't be seen as crystals. "Cryptocrystalline" quartz is the proper term. Agates and jaspers are part of the chalcedony group, and it's often difficult to tell them apart.

Here is what the experts say are the important differences between them.

-

Agates are formed in concentric rings. There are arguments about WHY this is true.

-

Jaspers may be striped or include circles, curves or other patterns. They are rarely only one solid color.

-

Agates are more porous than jaspers. Hence they are often dyed to produce striking colors.

-

A thin slice of agate may be translucent. You can see light through it. This is never true of a jasper.

So...now that you know all this, the question is why you should care. The real answer it that these factors help narrow your choices in a very large field. Each stone of either kind is truly unique. In short, both the differences and the reason they are loved by most people as one-of-a-kind treasures is pattern, pattern, pattern. A distant second may be color.

Because agates and jaspers are widely distributed and relatively easy to find, they are (usually) rather inexpensive. Price and pattern make them truly striking "signature" pieces that can be obtained by anyone.

Picture credit: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Jasper.pebble.600pix.bkg.jpg

Stones That Play With Light

While I believe almost any gemstone is phenomenal, some gemstones show what the experts call "phenomena" - straight lines, asterisms, schiller, fluorescence, adularescence, labradorescence and others. The common element among all these "isms" is surprise. A relatively ordinary-looking stone is turned or a light is moved and... suddenly something unexpected jumps out at you. WOW!

While I believe almost any gemstone is phenomenal, some gemstones show what the experts call "phenomena" - straight lines, asterisms, schiller, fluorescence, adularescence, labradorescence and others. The common element among all these "isms" is surprise. A relatively ordinary-looking stone is turned or a light is moved and... suddenly something unexpected jumps out at you. WOW!

Lines are among the easiest to find and to explain. Some stones that are single-color have a line of a different color running right down the middle. The line seems to move across the stone as the stone is turned relative to the light source.

A line inside a stone is actually an oriented inclusion. The included material deals with light differently from the stone, hence we see a different color. Lines are often referred to as "cats' eyes" - and some of them even seem to "blink" at you. Pretty strange. But fascinating.

"Stars" (asterisms) are better known (and more frequently imitated) than single lines, but they are really a similar phenomenon. In these, the included mineral is generally rutile, the same material found in some quartzes. In corundums - rubies and sapphires - the rultile forms a six-legged star that centers at the top of the stone and has roughly equal width "legs", each of which reaches to the bottom of the cabochon-cut stone. In diopsides, there are only four "legs". Other "star" stones are equally rare.

Many of the other phenomena are due to the layering of the included material at an angle to the outside of the stone. Labradorite and moonstone look like gray and white stones, respectively. When they move... Surprise! There are brilliant shades of blues under the outside gray or white! No matter how often you see it, there's always surprise.

The really amazing thing about the "lined" stones is that the person who cut and polished the stone had to have seen the inclusion and had to create the shape of the (cabochon) stone to maximize the effect. (I'd sure hate to be the person who wrecked a rare, natural star sapphire by not getting the star in the right place...)

The rarest of all phenomena is color change. Many stones seem to shift a bit in color as you look at them from different angles. True color-change gems (alexandrite, garnet, etc.) actually react to the different colors of the kind of light in which you see them. Alexandrite, for example, looks like an "emerald by day" (green) and a "ruby by night" (pink/red). The change is instantaneous - as soon as you walk outside or inside. The intensity of the change has to do with the mix of elements inside the stone. Degree of color change is subjective, but greatly affects value. If anyone ever offers you a decent-sized alexandrite for a price we could afford, have the thing tested by an expert before you even think about buying.

Picture credit: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/cf/LabradoritD.jpg

Stuff In Quartz

Quartz is among the most common minerals in the Earth's crust - about 12%. Quartz is also very hard stuff - 7 on the Mohs hardness scale * (where only diamond rates a 10). Normally trace elements in a stone are what produces the stone's body color.

Quartz is among the most common minerals in the Earth's crust - about 12%. Quartz is also very hard stuff - 7 on the Mohs hardness scale * (where only diamond rates a 10). Normally trace elements in a stone are what produces the stone's body color.

Amethyst, for example, is purple quartz, colored by iron. Under certain conditions though - heat, pressure, other minerals around it - any number of minerals can be included in otherwise clear quartz or light-colored quartz. This happens so frequently that a whole category of gemstones is informally referred to as "stuff in quartz".

While inclusions in gemstones are usually a negative, this is often untrue with quartz. While you want a flawless diamond (if you can get it), you may just fall in love with the uniqueness and patterns of the "stuff" found in quartzes. No "stuff-in-quartz" stone looks precisely like any other on Earth. Rather like snowflakes in that respect. Designers love them because each is unique. Wearers and collectors love them for that reason as well, but also because many stones in the category are affordable and just plain striking. In some, you can imagine pictures or plants.

Common "stuff-in-quartz" stones have inclusions of (relatively) softer rutile (Mohs scale 6), while tourmilinated quartz can be striking with black needles of schorl (black tourmaline) running through an otherwise clear stone. Less common but still fairly easy to find on the market are dendritic quartz, pyrite ("fools' gold") in quartz or even bits of brighter, contrasting colors - strawberry reds, medusa blues and others.

Some stuff-in-quartz stones are even stranger. They have inclusions of "negative crystals" - spaces where there once was a crystal of something, but the crystal itself never grew properly, merged into the stone, evaporated or otherwise disappeared. What you see is the shape of the included "crystal", but the shape is empty - a bit of "shaped nothing" inside the stone.

Most stuff-in-quartz stones are cut as cabochons, made to show the inclusions in their best light. Given this, you probably want as much light as possible to have access to the stone. Rather than setting yours in a closed backing then, consider "framing" the stone or having it set higher above the rest of your piece so that it can get light from all around it.

I can almost guarantee that the more you look at the stuff-in-quartz piece that caught your eye, the more you will grow to see and enjoy its uniqueness. Have fun looking! Or buying...

Picture credit: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Amethyst._Magaliesburg,_South_Africa.jpg

* The Mohs scale of mineral hardness characterizes the scratch resistance of various minerals through the ability of a harder material to scratch a softer material. It was created in 1812 by the German mineralogist Friedrich Mohs. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohs_scale_of_mineral_hardness